Marie Girault

Please, scroll down for English and Hungarian version.

Marie Girault

Artension Magazine n.114., P., 26-27.

2012 06

Par Marie Girault

« Stupeur et tremblements »

Titre emprunté á Amélie Nothomb

Magnétique et luminescente, l'oeuvre hypnotise. Attila Szűcs peint le plaisir empęché. L'embrasement, c'est pour quand ? Pour les figures, c'est Magritte et Füssli : un monde réinventé entre songe et cauchemar. Pour le retour du refoulé, á chacun ses fantasmes. Le coďt en peinture, c'est quoi ?

Scories précieuses

Le désir suspendu, éternellement, voilá ce qu'Attila Szűcs donne á voir en peinture. Dans la toile Faire la planche ; face contre terre, tétanisé, le corps semble planer á six pieds loin du sol ; en lévitation au-dessus d'une double cartouche de gaz.

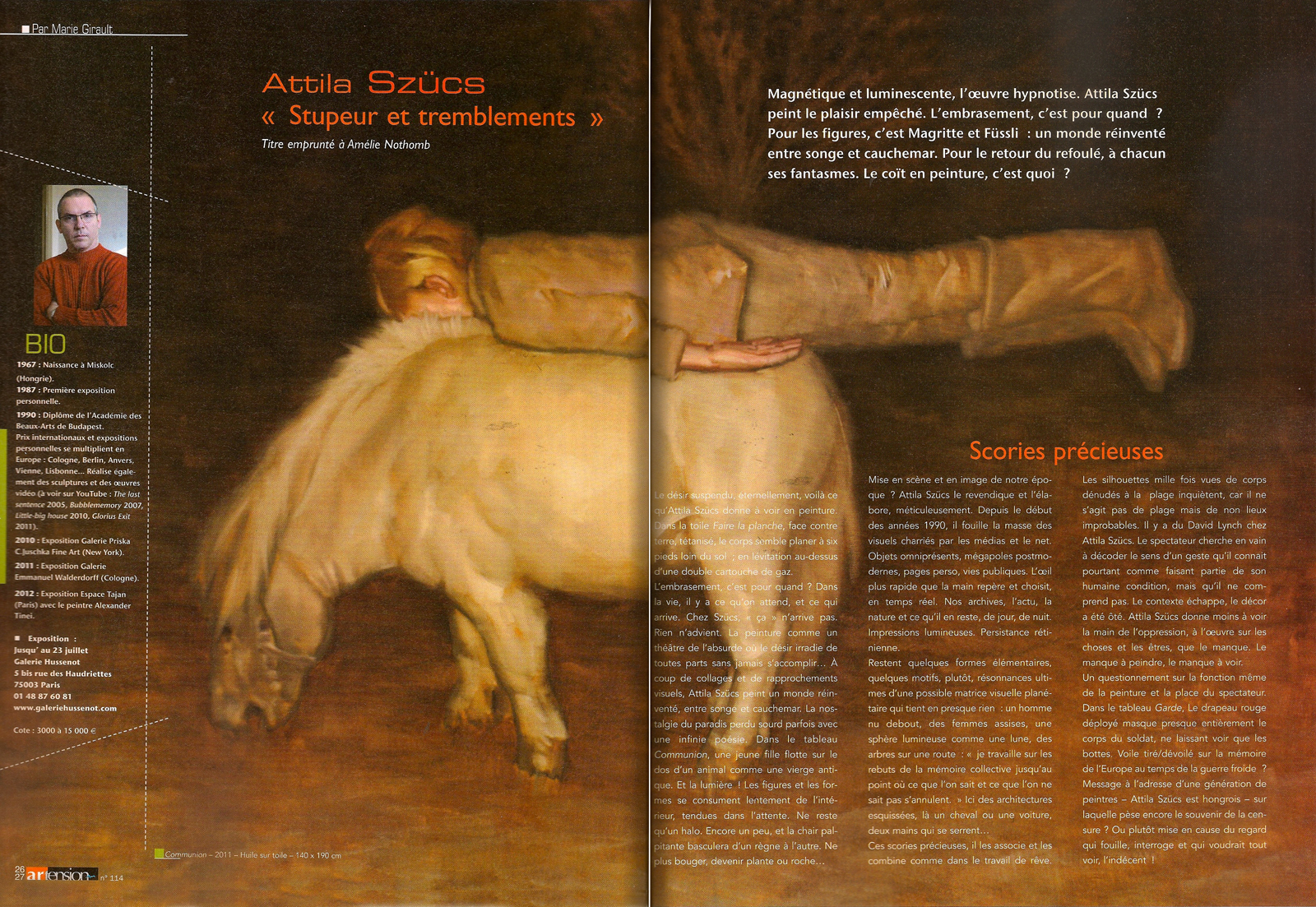

L'embrasement, c'est pour quand ? Dans la vie, il y a ce qu'on attend, et ce qui arrive. Chez Szűcs, « ça » n'arrive pas. Rien n'advient. La peinture comme un théâtre de l'absurde oů le désir irradie de toutes parts sans jamais s'accomplir... Á coup de collages et de rapprochements visuels, Attila Szűcs peint un monde réinventé, entre songe et cauchemar. La nostalgie du paradis perdu sourd parfois avec une infinie poésie. Dans le tableau Communion, une jeune fille flotte sur le dos d'un animal comme une vierge antique. Et la lumiére ! Les figures et les formes se consument lentement de l'intérieur, tendues dans l'attente. Ne reste qu'un halo. Encore un peu, et la chair palpitante basculera d'un rčgne ŕ l'autre. Ne plus bouger, devenir plante ou roche...

Mise en scéne et en image de notre époque ? Attila Szűcs le revendique et l'élabore, méticuleusement. Depuis le début des années 1990, il fouille la masse des visuels charriés par les média et le net. Objets omniprésents, mégapoles postmodernes, pages perso, vies publiques. L'oeil plus rapide que la main repčre et choisit, en temps réel. Nos archives, l'actu, la nature et ce qu'il en reste, de jour, de nuit. Impressions lumineuses. Persistance rétinienne.

Restent quelques formes élémentaires, quelques motifs, plutôt, résonnances ultimes d'une possible matrice visuelle planétaire qui tient en presque rien : un homme nu debout, des femmes assises, une sphčre lumineuse comme une lune, des arbres sur une route : « je travaille sur les rebus de la mémoire collective jusqu'au point oů ce que l'on sait et ce que l'on ne sait pas s'annulent. » Ici des architectures esquissées, lá un cheval ou une voiture, deux mains qui se serrent...

Ces scories précieuses, il les associe et les combine comme dans le travail de ręve.

Les silhouettes mille fois vues de corps dénudés á la plage inquiétent, car il ne s'agit pas de plage mais de non lieux improbables. Il y a du David Lynch chez Attila Szűcs. Le spectateur cherche en vain á décoder le sens d'un geste qu'il connait pourtant comme faisant partie de son humaine condition, mais qu'il ne comprend pas. Le contexte échappe, le décor a été ôté. Attila Szűcs donne moins á voir la main de l'oppression, ŕ l'oeuvre sur les choses et les ętres, que le manque. Le manque ŕ peindre, le manque á voir.

Un questionnement sur la fonction męme de la peinture et la place du spectateur. Dans le tableau Garde, Le drapeau rouge déployé masque presque entičrement le corps du soldat, ne laissant voir que les bottes. Voile tiré/dévoilé sur la mémoire de l'Europe au temps de la guerre froide ? Message á l'adresse d'une génération de peintres Attila Szűcs est hongrois sur laquelle pčse encore le souvenir de la censure ? Ou plutôt mis en cause du regard qui fouille, interroge et qui voudrait tout voir, l'indécent !

2012, p. 26-27 ARTENSION n° 114

"Stupor and Trembling"

Title borrowed from Amélie Nothomb

Magnetic and luminescent, the work hypnotizes. Attila Szűcs paints suppressed pleasure. When will the conflagration take place? For the figures, it's Magritte and Füssli: a reinvented world between dream and nightmare. For the return of the repressed, each to their own fantasies. What is coitus in painting?

Suspended desire, eternally, this is what Attila Szűcs guesses to see in painting. In the canvas Faire la planche, face down, paralyzed, the body seems to hover six feet above the ground, levitating above a double gas cartridge. When will the conflagration take place? In life, there is what we wait for, and what happens. With Szűcs, this doesn't happen. Nothing happens. Painting is like a theater of the absurd where desire radiates from all sides without ever being fulfilled... Through collages and visual comparisons, Attila Szűcs paints a reinvented world, between dream and nightmare. The nostalgia for paradise lost sometimes wells up with infinite poetry. In the painting Communion, a young girl floats on the back of an animal like an ancient virgin. And the light! The figures and forms slowly burn from within, tense in anticipation. Only a halo remains. A little longer, and the palpitating flesh will shift from one realm to another. No longer move, become plant or rock.

Staging and visualizing our era? Attila Szűcs claims it and elaborates it meticulously. Since the early 1990s, he has been combing through the mass of visuals carried by the media and the internet. Ubiquitous objects, postmodern megacities, personal pages, public lives. The eye, quicker than the hand, spots and selects, in real time. Our archives, current events, nature and what remains of it, day and night. Luminous impressions. Persistence of vision.

A few elementary forms remain, a few motifs, rather, ultimate resonances of a possible planetary visual matrix that contains almost nothing: a standing naked man, seated women, a luminous sphere like a moon, trees on a road. I work on the scraps of collective memory to the point where what we know and what we don't know cancel each other out. Here, sketched architectures, there, a horse or a carriage, two hands clasping...

He combines and assembles these precious scraps as if in a dream.

The thousand-times-seen silhouettes of naked bodies on the beach are disturbing, because they are not beaches but improbable non-places. There is something of David Lynch in Attila Szűcs. The viewer seeks in vain to decode the meaning of a gesture that he nevertheless knows as part of his human condition, but which he does not understand. The context escapes, the gap has been removed. Attila Szűcs shows less the hand of oppression, at work on things and beings, than the lack. The lack to paint, the lack to voice. A questioning of the very function of painting and the place of the viewer. In the painting Guard, the unfurled red flag almost entirely masks the soldier's body, leaving only the boots visible. A veil drawn/unveiled on the memory of Europe during the Cold War? A message to a generation of painters—Attila Szűcs is Hungarian—still burdened by the memory of censorship? Or rather, a challenge to the gaze that searches, questions, and seeks to see everything.

The indecent!

2012, p. 26-27 ARTENSION n° 114

"Kábultság és remegés"

A cím Amélie Nothombtól kölcsönzött

Mágneses és fénylő, az alkotás hipnotizál. Szűcs Attila elfojtott gyönyört fest. Mikor következik be a tűzvész? Az alakok Magritte-ot és Füsslit idézik: egy újraalkotott világ álom és rémálom között. Az elfojtott dolgok visszatéréséhez mindenkinek megvannak a maga fantáziái. Mi a közösülés a festészetben?

Felfüggesztett vágy, örökkévalóan – Szűcs Attila ezt véli felfedezni a festészetben. A Faire la planche (Lebegés) című vásznon egy arccal lefelé fekvő, megbénult test látszólag hat láb magasan lebeg a föld felett, egy dupla gázpalack fölött levitálva. Mikor következik be a tűzvész? Az életben van az, amire várunk, és van az, ami megtörténik. Szűcsnél ez nem történik meg. Semmi sem történik. A festészet olyan, mint egy abszurd színház, ahol a vágy minden irányból árad, anélkül, hogy valaha is beteljesülne…

Kollázsokon és vizuális összehasonlításokon keresztül Szűcs Attila egy újraalkotott világot fest, álom és rémálom között. Az elveszett paradicsom iránti nosztalgia néha végtelen költőiséggel tör fel. A Communion (Áldozás) című festményen egy fiatal lány egy állat hátán lebeg, mint egy ősi szűz. És a fény! Az alakok és formák lassan belülről égnek, feszülten a várakozástól. Csak egy dicsfény marad. Még egy kicsi, és a lüktető hús átlép egyik birodalomból a másikba. Többé nem mozdulni, növénnyé vagy kővé válni.

Korunk színpadra állítása és megjelenítése? Szűcs Attila ezt vállalja és aprólékosan kidolgozza. A kilencvenes évek eleje óta fésüli át a média és az internet által hordozott vizuális anyagok tömegét. Mindenütt jelenlévő tárgyak, posztmodern megapoliszok, személyes oldalak, nyilvános életek. A szem, gyorsabb, mint a kéz, valós időben észlel és válogat. Archívumaink, aktuális események, a természet és ami megmaradt belőle, éjjel-nappal. Fénylő benyomások. A látás perzisztenciája.

Néhány elemi forma marad, vagy inkább néhány motívum, egy lehetséges planetáris vizuális mátrix végső rezonanciái, amely szinte semmit sem tartalmaz: egy álló meztelen férfi, ülő nők, egy holdszerű fénylő gömb, fák az út mentén. „A kollektív emlékezet foszlányain dolgozom addig a pontig, ahol az, amit tudunk, és az, amit nem tudunk, kioltja egymást.” Itt vázlatos épületek, ott egy ló vagy egy kocsi, két egymásba kulcsolódó kéz…

Ezeket az értékes foszlányokat úgy kombinálja és illeszti össze, mintha álomban tenné.

A parton álló meztelen testek ezerszer látott sziluettjei nyugtalanítóak, mert azok nem strandok, hanem valószínűtlen nem-helyek. Van valami David Lynch-re emlékeztető Szűcs Attilában. A néző hiába próbálja dekódolni egy gesztus jelentését, amelyet jóllehet emberi mivoltának részeként ismer, mégsem ért. A kontextus elillan, az értelmezés tere megszűnt. Szűcs Attila kevésbé a dolgokon és lényeken munkálkodó elnyomás kezét mutatja meg, mint inkább a hiányt. A festés hiányát, a megszólalás hiányát. A festészet valódi funkciójának és a néző helyének megkérdőjelezése. Az Őr (Guard) című festményen a kibontott vörös zászló szinte teljesen eltakarja a katona testét, csupán a csizmája látszik. Fátyol borul/fellebben Európa hidegháborús emlékezetére? Üzenet festők egy nemzedékének – Szűcs Attila magyar –, akiket még mindig nyomaszt a cenzúra emléke? Vagy inkább kihívás a kutató, kérdező, mindent látni akaró tekintet számára.

A szemérmetlen!

2012, p. 26-27 ARTENSION n° 114